It’s been more than six and a half years since The Passion of the Christ was released. I still have not seen it. This is by choice, not by chance. Since I am writing a series of reviews of all the major films that portray the story of Jesus, I thought I should explain why this one – by far the most popular and highest-grossing Jesus movie ever – is being omitted, at least for the time being.

My reasons are both personal and theological. Let me say at the outset that my reasons have nothing to do with the man who made the film, Mel Gibson. Even though I think his personal life indicates that he is a deeply troubled man with some serious failings, that alone would not keep me from seeing it. After all, Richard Wagner was at least as flawed, and I listen to his music. Also, the fact that the film was controversial would not have kept me away. The Last Temptation of Christ was also controversial, and I saw it. More on this point later.

The film was released three months, almost to the day, after the death of our 13-year-old son in an automobile accident. At the time our 11-year-old daughter had just awoken from two and a half months in a coma, and my wife was living at the hospital with her. At this point any sensible person would say that alone was reason enough why I wouldn’t go running off to the movies. But actually, just once I had gone to the movies (The Return of the King). And I wish I hadn’t, at least when I did. But one typically considers seeing a movie when everyone else is seeing it, when it is being widely discussed and, in this case, debated.

I went though a lot of anguish and inner struggle over having lost my son. As a Christian, it was not a crisis of faith so much as a trial of faith. I felt like the soldier on the battlefield who is having his leg amputated after the anesthetic has run out. I know I can live through it, and know I must endure it, but that does not take the pain away. Will the fire refine me or burn me up?

One thought that kept recurring was that God the Father had also lost His Son to the grave. I would always think, “Yes, but that was only for three days; this is for the rest of our lives.” I eventually came to believe that the difference I perceive between three days and the rest of my life will someday evaporate in light of eternity. If you were to say, “But God knew that His Son’s death was only temporary,” I would say, “So do I.”

All of this to say, I couldn’t contemplate watching a whole movie that focused on Jesus’ death. Death had gutted me: I’d had enough of it. “Well, it wasn’t just any death. Maybe it would have helped.” I doubt it.

Another reason: I was horrified at reports of people walking into the theater with their little kids, buckets of popcorn and half-liters of pop as if they settling in for Toy Story. This is not just a movie, and it is certainly not for the little ones. This is like Schindler’s List or Saving Private Ryan. It calls you to witness a harrowing portrayal of suffering that will not amuse you. It is not entertainment. Perhaps in a few months I could sit through such an experience, but I could not sit with such an audience. I certainly could not abide people subjecting their children to such an ordeal. I would have to watch it alone.

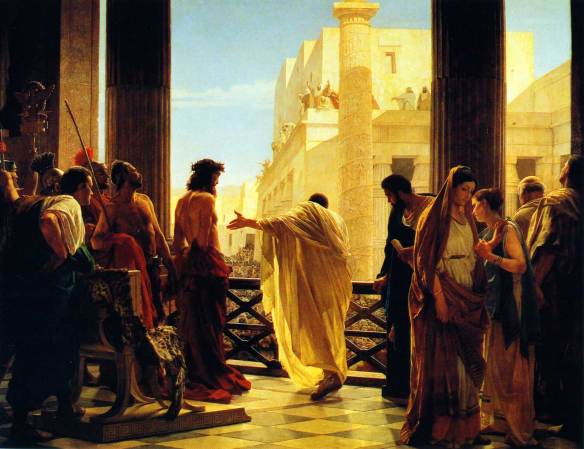

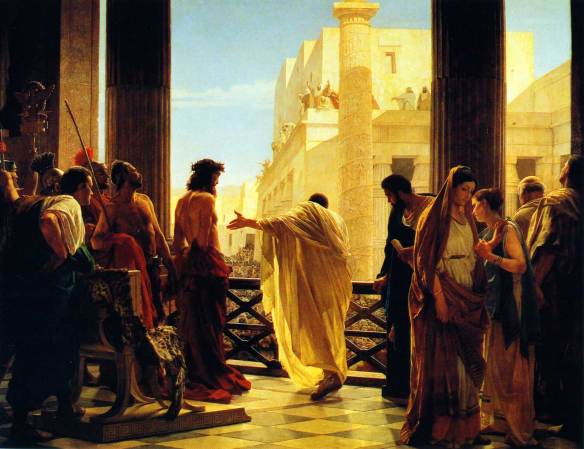

I know that the movie was charged with portrayals that some took as anti-Jewish (The movie had Jewish defenders as well as detractors). Without having seen the movie, let me assume that it reflects the gospel narratives. The gospels have a polemic nature, so there are antagonists and protagonists. It should be pointed out that while some of the antagonists are Jews, practically all of the protagonists are. But more significant is that, while in Jesus’ arrest and trials the key actors are the Jewish leaders, in his execution there is a clear and necessary joining of Jewish power and Gentile (Roman) power. Any fair reading of the texts would bear this out. This fact also has a theological significance for the early church:

So when they (the Christians) heard that, they raised their voice to God with one accord and said: “Lord, You are God, who made heaven and earth and the sea, and all that is in them, who by the mouth of Your servant David have said:

‘Why did the nations (Gentiles) rage,

And the people plot vain things?

The kings of the earth took their stand,

And the rulers were gathered together

Against the LORD and against His Christ.’

For truly against Your holy Servant Jesus, whom You anointed, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, with the Gentiles and the people of Israel, were gathered together to do whatever Your hand and Your purpose determined before to be done.” (Acts 4:24-28 NKJV)(Parentheticals mine.)

Jew and Gentile, who were separate and opposed, came together in agreement that Jesus should die. In this collaboration they represent all of humanity. Luke, the only Gentile NT writer, makes a point of telling us,

That very day Pilate and Herod became friends with each other, for previously they had been at enmity with each other. Lk. 23:12

Of course, I would have to see the movie to know for sure, but if the charge is that the movie is anti-Jewish because the New Testament is, I don’t accept the premise. Just because the Jewish leaders are villains does not make the narrative anti-Jewish. All the the heroes are Jewish as well – not the least the rabbi Yeshua himself.

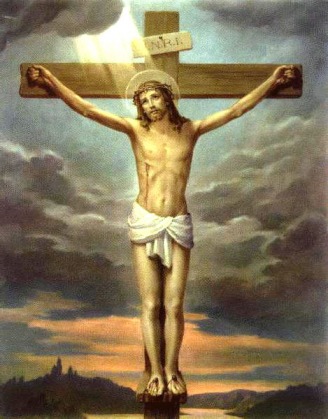

Finally, my interest in the film is dampened by by the apparent emphasis it has on the gruesome nature of Christ’s sufferings. I have no doubt that the torture and mutilation it shows is without exaggeration. I have seen plenty of stills, and a few clips from the movie. I have also seen most of the major Jesus movies, with their typically mild depiction of the passion. Tiny stripes with little streaks of blood. This is for two obvious reasons that I can think of and one less obvious. The audiences and the level of violence that both they and the censors (when they reigned) would have tolerated would not permit of a graphic rendering of Jesus’ torture. Second, most people would like to consider the story of Jesus a family movie, and not want the little children of the world to be exposed to such horrors. The less obvious reason is that most Jesus movies, from the silent era on, drew their imagery and staging from Christian iconography – most commendably from great renaissance painting and sculpture…

…and more regrettably from lesser forms of popular art, like those found in old family bibles or on prayer cards.

The Passion is to those sanitized portraits, I imagine, what P.O.D. is to Evie.

But I think there is an even more important consideration. I have sat through at least a half dozen sermons in my life that did in words what The Passion has done on film: draw attention to the gore and mutilation of the passion. The speaker usually goes for the effect of horror or revulsion and then says something to the effect of, “He suffered all of this for you.”

And it’s true. He did suffer these things on behalf of everyone of us. The New Testament says this very clearly, and I do not disagree. But what it does not include is any of the vivid details. That’s because it was neither necessary – most readers and hearers were all too familiar with the cruel practices of the day – nor was it central to the point of His sufferings.

The meaning of His suffering is profound, and it is considered from more than one perspective in the NT. We are to understand it as the ultimate form of humilty and obedience.

And being found in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself and became obedient to the point of death, even the death of the cross. Php. 2:8

It is a model of suffering for us, that is, it makes our character and conforms it more to Christ’s.

For consider Him who endured such hostility from sinners against Himself, lest you become weary and discouraged in your souls. Heb. 12:3

It paid the penalty in full for all the sins of the world.

For Christ also suffered once for sins, the just for the unjust, that He might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive by the Spirit…1Pe. 3:18

And He Himself is the propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the whole world. 1Jn. 2:2

It reveals the full extent of God’s love for humanity.

In this is love, not that we loved God, but that He loved us and sent His Son to be the propitiation for our sins. 1Jn. 4:10

To understand this should not require – and apparently the writers of the NT agreed – a detailed mental image of butchery and mutilation. The point of His torture and death is spiritual and theological not physiological. To have witnessed the events would have elicited an R-rating, but to understand what they meant in the fullest sense certainly does not.

Perhaps someday I may feel differently about the prospect of watching The Passion of the Christ. From what I have read, it is an extraordinary film. But it is hard for me to foresee gaining so much from it that it would outweigh the ordeal of watching it.