Mother, do you think they’ll drop the bomb?

-Roger Waters, “Mother”

On Easter Sunday, 1980, I proceeded a with a group of protesters across a point of no return at the main entrance to Malmstrom Air Force Base near Great Falls. We walked forward deliberately and slowly against the previously delivered warning of the airmen guarding the gate.

On Easter Sunday, 1980, I proceeded a with a group of protesters across a point of no return at the main entrance to Malmstrom Air Force Base near Great Falls. We walked forward deliberately and slowly against the previously delivered warning of the airmen guarding the gate.

We had come in protest to the presence around Malmstrom of the largest missile field in North America. Over this vast area in north central Montana the rolling grassland was dotted with over 200 underground silos, each the home to a Minuteman ICBM armed with warheads capable of unimaginable destruction : city-killers. They were all aimed at targets in the Soviet Union. Undoubtedly, somewhere in the USSR, there were missiles pointing not only at US targets, but directly at this missile field.

We had come in protest to the presence around Malmstrom of the largest missile field in North America. Over this vast area in north central Montana the rolling grassland was dotted with over 200 underground silos, each the home to a Minuteman ICBM armed with warheads capable of unimaginable destruction : city-killers. They were all aimed at targets in the Soviet Union. Undoubtedly, somewhere in the USSR, there were missiles pointing not only at US targets, but directly at this missile field.

At 16, I was the youngest among the protesters. As we walked in a straight line over the threshold, we were arrested and taken to a holding room.

It was a combination of fear, anger and conviction that drove me to join this group and decide to get myself arrested in protest. But it originated wholly of fear, when I was ten years old. I remember the day.

It was in the fall of 1973, and I was in my first months at the Open Community School. The Middle Group (mostly 2nd, 3rd and 4th graders) was shown a 1972 documentary film based on Alvin Toffler’s best-selling book, Future Shock.

It was in the fall of 1973, and I was in my first months at the Open Community School. The Middle Group (mostly 2nd, 3rd and 4th graders) was shown a 1972 documentary film based on Alvin Toffler’s best-selling book, Future Shock.

It was narrated by Orson Welles, and had the effect (on me, at least) of a dead-certain prediction of things to come. At times silly and dated, and full of what are now pop-sociology cliches, it was nevertheless disturbing and at moments terrifying, as was the opening montage. Imagine how it looked to 8-, 9- and 10 -year- olds!

It warned of cyborgs, human clones, social disintegration and technological change running “out of control.” In the latter part of the film, we see some protesters chanting, “Ban the bomb!” followed by Welles: “Sometimes technology can destroy. Amchitka. An underground nuclear explosion. When will the next nuclear blast occur, and what will it do to us?” A few minutes later Toffler was on camera, saying to some college students, “…The technology is so powerful and so rapid, it could destroy us if we don’t control it.”

This was the first I had heard of nuclear weapons and the threat they posed to us. After the film our teacher explained a little about the arms race, weapons stockpiles, and the MAD (‘mutually assured destruction’) doctrine.

Well, I was deeply troubled. We were talking, after all, about the end of the world. If that weren’t enough to rock my ten-year-old world, we were later treated to another documentary.

About Hiroshima.

At the A-Bomb (Genbaku) Dome, Hiroshima Peace Memorial, 1991

I have not been able to track this film down, but I do know that it incorporated footage of the aftermath that had only just been declassified by the US Government in 1973. The film showed horrific images of the dead and dying, and survivors of the atomic blast. I’d never seen anything even remotely as appalling or frightening.

We were told that the superpowers possessed enough weapons – even hundreds of times more destructive than the Hiroshima bomb – to kill every person on the planet a hundred times over, and if we got into a war with the USSR, the world would be consumed in a global nuclear annihilation.

Wow. Bummer!

This was the worst news I’d ever heard. It haunted me for the next eight years. The following school year I was spending the night at the rural home of my friend, Todd Mecklem. We always stayed up and watched Sinister Cinema, but rarely made it through the second feature. As I slept, I dreamed.

I was sitting on the steps of our house. There was the sound of an air raid siren, and prop planes overhead. Someone pointed at a plane in the sky. Next, I was heading for shelter. I entered a large room with high ceilings. It looked like a bank lobby, with the curtains drawn over large windows. Scores of people were crowded in and sitting on the seats and the floor. I saw my mom, and sat with her. Dread filled the room, I felt it. We were waiting. Waiting for the bombs to drop. I knew if they did, it was the end.

That was the first nightmare I had about imminent nuclear doom, but not the last. The others were just variations: with my dad, in a car, racing for shelter — and the blinding flash.

As I thought about it I realized that what really troubled me was not the prospect of death by itself; even for a kid, my own death was not nearly as terrible as the death of everyone, the whole world.

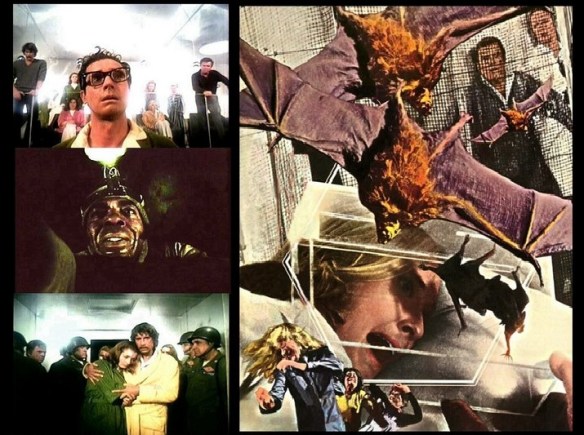

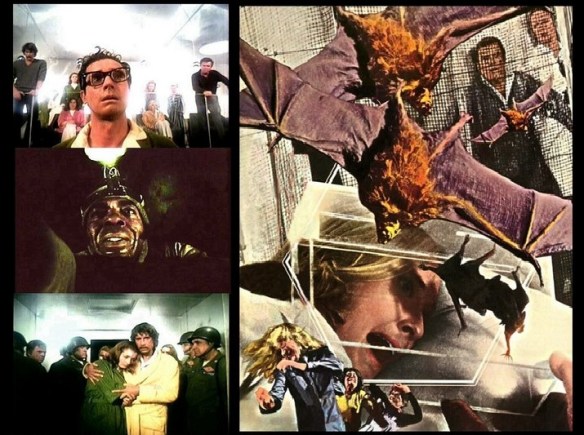

Chosen Survivors (1974). They escaped nuclear conflagration against their will, only to be overrun by killer bats. The irony!

Over the years, my fear was fueled by movies such as the Planet of the Apes series, The Omega Man, Logan’s Run, Chosen Survivors (one of the worst movies I’ve ever seen), Dr. Strangelove, and Peter Watkins’ The War Game. I seemed to keep hearing that the future promised either: untold wonders of technological advances, space travel, medical miracles, etc. — or: total annihilation. As I got older and the fabulous space age did not emerge, it was looking like the annihilation-thingy was only a matter of time.

I don’t feel safe in this world no more

I don’t want to die in nuclear war

I want to sail away to distant shore

-Ray Davies, “Apeman”

When I was a sophomore in high school, I saw a documentary on the arms race featuring a retired US Army colonel who was an antinuclear activist. I began to see how I could turn what was only helpless fear into activism and hope. I figured if you saw something wrong with the world you should work to fix it or sit down and shut up. And what was wrong with the world in my view was the existence of the weapons. So the obvious solution was to get rid of them, was it not? I decided to inform myself. I sent away to Sojourners, and they sent me a packet with articles, ideas for activism, and a map. As I unfolded it, it revealed the contiguous US and drawn on the map were all the nuclear targets in the event of a full exchange with the USSR. In Montana, where I now lived, it showed a huge area that represented the Minuteman missile field near Great Falls. The intent of the map was clear. In that, it was successful. My fear was refreshed, and outrage was now added, and I set about seeing what I could do.

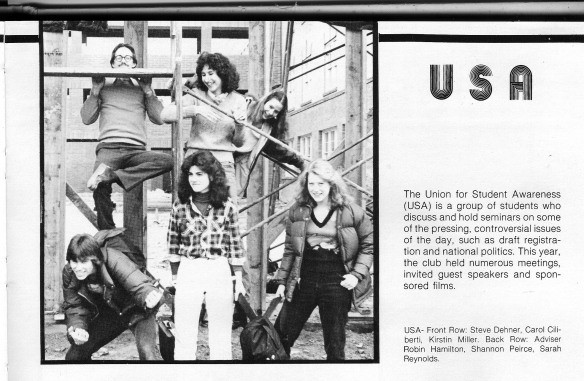

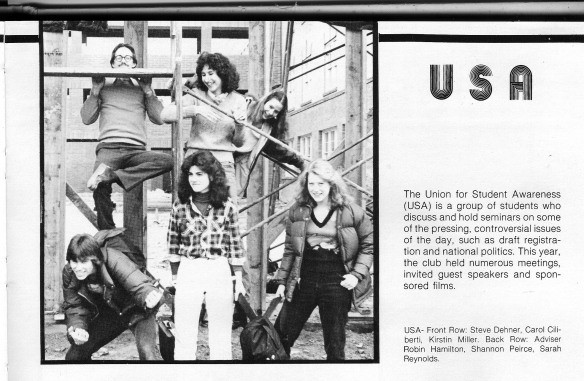

I became associated with leftwing activists at the University of Montana, the Student Action Center. I started a polital action club at Hellgate that I modeled after SAC: the Union for Student Awareness (USA).

I asked my English teacher, Robin Hamilton, to serve as advisor. He now serves in the Montana legislature.

SAC was planning an action for Easter (April 6) preceded by a week of meetings and forums on war & peace issues. On Monday, March 31st, the week’s featured speaker appeared on campus: Philip Berrigan, half of the famous Berrigan Brothers, the anti-war clergy-activists of the 60s and 70s. Just five months later they would launch the Plowshares Movement. In between noon and 8pm talks, he met with SAC and those would participate in the Easter Vigil action. We asked him questions about civil disobedience and the issues of the day. I told him I was planning to get arrested on Sunday, and he commended me for it.

Two fingers, right? 1970, age 7.

It felt great to have a legend of the anti-war era, a man who spent years in jail for acting on his convictions, give me a pat on the back. But there was another person whose approval meant a lot more to me than Phil Berrigan’s: my Dad. He too was an anti-war activist who went to jail for his protests, and as a 7- and 8-year-old, I had accompanied him to planning meetings, marches and pickets. In finding what I thought was a good outlet for my anti-nuke feelings, I had also found a way to emulate Dad. Secretly, I hoped it would earn his respect, something most boys crave from their fathers.

On Saturday night they offered a free showing of the famous 1974 anti-Vietnam war documentary, Hearts and Minds, another film that I (again, alarmingly) had seen when I was about 12. The film was going to be delivered on Friday, so I asked SAC if I could show it Friday night at Hellgate. They agreed, as long as I confined my advertising to the high school. I plastered fliers all over the school with just a day or two’s notice. I had to go over to the U campus and walk the film back to school, a herculean task I was barely able to manage. We had an enormous turnout and it was the most successful event USA carried off. Late that night I walked the reels back to the campus.

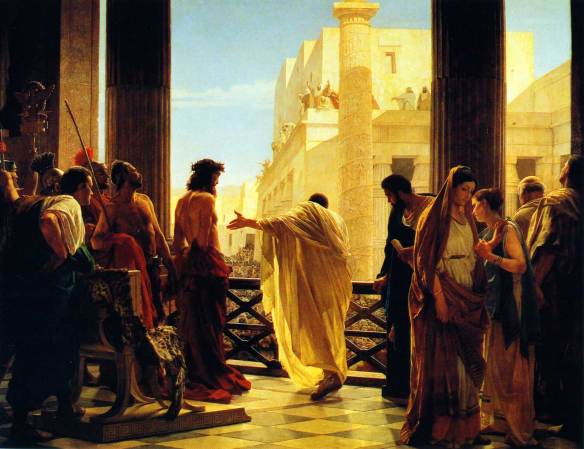

The Easter Vigil was led by John Lemnitzer, a Lutheran pastor, and Terry Messman from SAC. The group met on campus and we drove up to the the Base. The Vigil and the action were planned and intended as a Christian tesimony to the evil of war and its weapons. There were those in the group, including myself, however, who would not have identified themselves as Christians, but we would have agreed that the statement of the Vigil was in accordance with Christian teaching, and that was good enough for us. We stood outside the gate and sang a few songs. In particular I remember the one from the 20th Psalm:

The Easter Vigil was led by John Lemnitzer, a Lutheran pastor, and Terry Messman from SAC. The group met on campus and we drove up to the the Base. The Vigil and the action were planned and intended as a Christian tesimony to the evil of war and its weapons. There were those in the group, including myself, however, who would not have identified themselves as Christians, but we would have agreed that the statement of the Vigil was in accordance with Christian teaching, and that was good enough for us. We stood outside the gate and sang a few songs. In particular I remember the one from the 20th Psalm:

Some trust in chariots

And some in horses

But we will trust in the name of the Lord

When we crossed the line of trespass, the guards escorted us to some concrete room, where we spent hours being processed and awaiting our disposition. When I decided to get arrested, I had agreed to accept whatever charges and sentencing I might receive. I had my parents blessing in this. I did not know how it would turn out. At the end of the day all but John and Terry were released and no charges were brought against the rest of us.

When the final results were tallied, the nukes were still in their silos and we were going home with a great sense of satisfaction. But as any radical knows, that is not one’s general experience in life. A radical eventually comes up against the annoying little fact that hardly anybody in the world, even your non-radical friends, really see things the way you do: that’s why you’re called a radical. When I would venture to claim that we were in danger of incinerating the entire human race, I’d be met with, “Wow. Bummer!” and a shrug.

were going home with a great sense of satisfaction. But as any radical knows, that is not one’s general experience in life. A radical eventually comes up against the annoying little fact that hardly anybody in the world, even your non-radical friends, really see things the way you do: that’s why you’re called a radical. When I would venture to claim that we were in danger of incinerating the entire human race, I’d be met with, “Wow. Bummer!” and a shrug.

This failure of the rest of the world to see the outrage it should have leads to constant frustration. This is why radicals inevitably grow angry and resentful. They come to hate American society (If they didn’t already) for it’s moderate-to-conservative outlook, and their own inability to change it. “If no one can see things as I do, they must be morons! Or corrupt. Corrupt morons!” Americans in a nutshell, for your average radical.

I quickly started down this path. But I think I had some sense or at least some doubt about where it was heading. It may have been that I was just growing a little more pessimistic about social change. After the elections of 1980, it did not look as though things were going our way. That didn’t mean I wanted to give up, I just meant I would have to come to terms with things as they were.

That would have to include the finger of the maniacal, wild-eyed, warmongering Ronald Reagan resting on the “Blow-up-the-world” button. (As it turned out, few things have increased the security of the world as much as ending the Cold War without letting it erupting into a hot war. And history has given the primary credit for that feat to the warmonger Ronald Reagan.)

After my rebirth in 1982, I looked at the prospective end of the world in a very different way. I believe that God has committed to humanity the stewardship of the earth, but not its fate. Human history and its ultimate disposition are in His hands, not ours. But I also eventually came to look at weapons differently as well. Weapons alone are not fearful. The evil that can be done with them proceeds from the human heart, the ultimate weapon of mass destruction. A knife, a club, an airliner – they only pose a threat in the hands of someone of ill-will. Men as powerful as Hitler or Stalin had no atomic weapons before 1945, but look what they had done by then. Nukes have not been used since 1945, but we shouldn’t assume that it has nothing to do with the people and nations that have them. Turn just one nuke over to Ahmadinejad and you can march, chant, trespass, and pound nose cones all you want, but if you live in Tel Aviv, you’re dead.

In my view I wasted my time on any effort to get nuclear weapons out of the hands of responsible nations that would probably never use them. And as far as activism goes, it will never wrest such weapons from the nations or groups that would use them. You can only try to stop them from acquiring them and keep the price very high for using them. For that, you need the US government and its military forces.