#2: Motorcycles = Broken Body Parts.

Continuing my account of four things I learned through my short high school friendship with Steve Albini, I come to #2, which does not require much explanation. Steve rode a motorcycle. During his senior year (’79 -’80), Steve got creamed on his motorcycle by a larger motor vehicle. Steve’s leg got snapped like a pretzel. Come to think of it, his legs were pretzels. The straight kind, you know, like Mr. Salty.

Never, since I saw him in his hip-to-heel cast, and heard his account of the accident, have I wanted to own a motorcycle or ride on one going more than 15 miles per hour. That’s just how it is.

Lesson learned. Thanks, Steve.

It actually may have not been his only injury-accident on a bike, but my memory of that is fuzzy now. At least one account of Steve’s high school days says that he taught himself the bass guitar while he was incapacitated. I don’t recall that myself, but it does make a nice segue into #3, which is all about music and life.

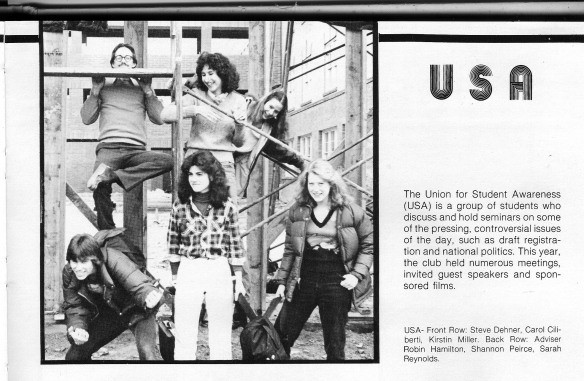

#3: Do it Yourself, Why Don’t You.

In March of 1983, I was living in Oklahoma City, and took a bus up to Chicago. I went up because Troy Deckert was getting married. Mark Hayes was living in Chicago as well, and at the time was staying with Steve. I don’t remember where I slept at night, but it seems we spent considerable time at Steve’s apartment. Steve was in his third year at Northwestern. I recall that when I first got there Steve was out of town.

When he returned he breezed into the apartment, explaining that he, “Just came from Madison, where I got my hair cut by a Neo-Nazi.”

I hadn’t seen him in two and a half years.Time was flying. Steve was flying. He was energetic, enthusiastic, apparently happier than he had been in Missoula. He seemed to have a lot of irons in the fire.

When he got there it was the first time the four of us had been together since December of 1980 in Missoula. That, I may as well add here, is when and where The John Lennon Story fits in.

It was my junior year at Hellgate High School, and I was struggling, academically and personally. One of the things I felt I had going for me was my work on the Lance, where I had Steve’s old position of Editorials Editor. In December, the murder of John Lennon was a real blow to me and several of my friends. We did not talk about it much, mostly I suppose, because we didn’t know what to say. I know I didn’t. It just sucked.

Steve came home to Missoula that week. I ran into him Saturday night at a “New Wave Festival” at the University, and asked him if he would write a guest column for the Lance. I thought it would be funny to see people’s reaction to its appearance when they thought they were finally rid of him for good. He balked at the idea. I pressed him and he relented.

The piece he turned in I felt compelled to publish, but I was the one who was cheesed off by it. There were two reasons. One: the thrust of the column was, “John Lennon is dead and I don’t care.” Two: he included an account of me asking him to write it that had me sounding like a complete dork. If Steve truly did not care what people thought of him, then I was his total opposite. I cared desperately what people thought, and I had pretty thin skin, too. I didn’t stop to think that nobody’s opinion of me would be formed by what he wrote. Some people would have considered it an honor to be called a “notorious hippie” in the same piece that said John Lennon was better off dead. But I felt the column had made of a fool of me, and it hurt my feelings because, even though we weren’t close, I considered Steve a friend – with good reason. At the same time I realized how ridiculous it would seem for me to vent my anger for the same period of time I felt it. I expressed my anger to my friends, who laughed it off, then kept it to myself. It seems to me now that it was Steve’s last chance to give high school the finger. I just happened to be standing in view.

If Steve truly did not care what people thought of him, then I was his total opposite. I cared desperately what people thought, and I had pretty thin skin, too. I didn’t stop to think that nobody’s opinion of me would be formed by what he wrote. Some people would have considered it an honor to be called a “notorious hippie” in the same piece that said John Lennon was better off dead. But I felt the column had made of a fool of me, and it hurt my feelings because, even though we weren’t close, I considered Steve a friend – with good reason. At the same time I realized how ridiculous it would seem for me to vent my anger for the same period of time I felt it. I expressed my anger to my friends, who laughed it off, then kept it to myself. It seems to me now that it was Steve’s last chance to give high school the finger. I just happened to be standing in view.

There’s a story our friend Deb Scherer tells, who also served on the Lance. She had a distinctive way of dressing. It was eclectic, it was funky, it was her own. Steve was giving her a hard time about it. This from the guy who came to school in his deliberately shredded pretzel-pants and similarly abused t-shirt on which he had painted in fire-engine red: “DIE!” Deb finally said to him, “I don’t care what you think of the way I dress!,” to which he replied, “Good, you shouldn’t!” Some of the things Steve did and said were undoubtedly expressed with this conviction in mind. Considerable vexation throughout the English-speaking world over the last 30 years could certainly have been avoided if others had shared it.

So, in 1983, that had been the last time I had seen or spoken with Steve. I was over it, but in the intervening years a lot had happened. Steve had heard that I had gone off into the Weirdlands and become a born-again Christian. Even more disconcerting, Troy, who was a closer friend to Steve, had come to Chicago the previous summer and done the same. I suppose you can imagine how completely insane some of our friends thought it was that we would both, at the same time, hundreds of miles apart, come to Jesus. Every time I saw one of my old friends, I expected to be “dealt a ration,” as we used to say. I expected the biggest ration of all to be dealt by Steve. I was waiting for it.

Steve showed me his apartment. The highlight of the tour, from Steve’s viewpoint, was in the kitchen, where he showed me Archie, a really huge and thankfully deceased cockroach. I’ve got to hand it to Steve Albini. Not only did he afford Archie the respect and honor he deserved, but he had enough taste and culture to preserve him for others to enjoy. As I admired the enormous blattoid, Steve said,”So Dehner, why Jesus?”

I was expecting something quite different, so the question caught me off guard, and I fumbled for something to say that would make sense. Actually, it was great question. It was perfectly respectful, and I should have been able to give a coherent answer. But what can I say? It had been nine months. I was nineteen years old. So I said something like, “Because He’s real. I have no doubt that He is…” Something like that.

“Huh.” He shrugged. And that was it. People who don’t know Steve might think, on account of his sometimes, um, forthright way of expressing his views in public, that he’d have given me or Troy a hard time. But regardless of what he might have thought, he had nothing mean or derogatory to say to me. Live and let live seemed more his style. He let a Nazi cut his hair. He let a Jesus freak see his cockroach.

Then Steve showed me a unfurnished bedroom, that had only some musical gear, his electric bass, his drummer Roland, and a box or two of 45rpm EPs.

“This is our record,” he said, pulling one out. “Here, have one.”

It was Big Black’s first record, Lungs. And it wasn’t really “our record,” it was his record. He made it.

No, I mean: he made the record.

![BIG-BLACK-LUNGS-(EP)-[Vinyl]](https://thefreerange.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/big-black-lungs-ep-vinyl.jpg?w=150&h=150) He wrote, played and sang (“i’m a steelworker, i kill what I eat”). He engineered, recorded and mixed. He took the photos and created the cover artwork and logo. Wrote the liner notes. Polymerized the vinyl compound with his own chemistry set and hand-etched the grooves in the disk (Actually, I think he might have hired this part out.). Packaged and delivered the records to local stores — with party favors enclosed for the lucky customers, so that opening your Big Black LP was the musical equivalent of Cracker Jacks (if you wouldn’t mind finding a bloody kleenex as your ‘toy surprise’).

He wrote, played and sang (“i’m a steelworker, i kill what I eat”). He engineered, recorded and mixed. He took the photos and created the cover artwork and logo. Wrote the liner notes. Polymerized the vinyl compound with his own chemistry set and hand-etched the grooves in the disk (Actually, I think he might have hired this part out.). Packaged and delivered the records to local stores — with party favors enclosed for the lucky customers, so that opening your Big Black LP was the musical equivalent of Cracker Jacks (if you wouldn’t mind finding a bloody kleenex as your ‘toy surprise’).

The point, that I’ve taken so long to get to, is that he didn’t ask anyone’s permission to make a record, and he didn’t wait for – or even pursue, as far as I know – a recording contract, either. He didn’t have someone looking over his shoulder telling him what he could or couldn’t say. He just made the thing himself. And he told anyone reading the insert to go make their own record, too. It was simply unacceptable to him that he would relinquish the control and freedom to make the music he wanted, and get ripped off in the process.

Using this approach, Steve pretty much made his musical career on his own terms. Further, he inspired others to do the same. This same spirit came to drive not only independent music, but indy film making as well, and made the Internet the ultimate democratized medium.

When I was struggling to make films in the 80s and 90s Steve’s literally homemade record pointed to the possibility of not only by-passing media gate-keepers, but also kicking down the gates. One of the things we talked about in August was the collapse of the recording industry as we’ve known it, and something much better (in Steve’s view) replacing it.

On Lungs, Steve had a friend named John Bohnen play the sax on one of the songs, and gave Mark credit for “more yells on dead billy.” He did everything else. Big Black was about to become a band, and this record helped put it together. But before Big Black was a band, even before Big Black was just Steve and some instruments – there was Just Ducky.

Next: #3 Part 2 – Just Ducky

part one. part three. part four.